To the boats:

What would you have done?

Anyone who has ever thought about Titanic's last night has at some point asked themselves, "What would I have done?"

Anyone who has ever thought about Titanic's last night has at some point asked themselves, "What would I have done?"Try to imagine yourself snug in your warm bed. You're on the largest ship in the world. The press -- even shipping trade journals like The Shipbuilder -- have declared this ship unsinkable.

At midnight, a steward knocks on your door and announces that you need to get dressed and report to the boat deck. Oh, and you need to bring your lifebelt. Is it a drill? It has to be a drill. The ship is as steady as ever. Warm air is still pouring out of the little space heater in your cabin. The electric lamps are still burning bright. The hum of the engines is gone, but it was so slight that you don't even notice.

After a few moments of quiet deliberation, you hear others clamoring down the hallway. You decide to get dressed and see what all the fuss is about. When you reach the grand staircase, that mountain of oak crowned by a bronze clock (symbolizing Honor and Glory Crowning Time) and capped by a magnificent wrought iron and glass dome, you realize it is preposterous. Everything about Titanic says permanence.

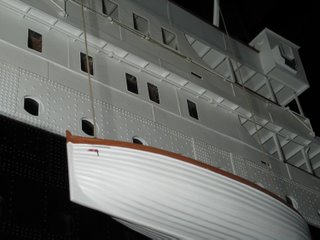

The band is playing ragtime when you reach the boat deck. A chill wind stops you in your tracks. Preposterous, you say again to yourself. Officers are calling for passengers to step into the lifeboats that have now been swung out into space over the side of the ship.

I'm a lot safer here than I am in that small boat, you think to yourself. You cross to the ship's side and look over the railing. It's nearly sixty feet down to the sea. It seems a perilous journey to make -- and a needless one. You notice a few passengers relunctantly getting into the boats. With only 28 people aboard, the first boat starts its jerky descent to the sea below. You hear the screams of the women as the davit ends bob up and down, shaking the boat and everyone in it. No thanks, you think to yourself.

Would you have taken a seat in the lifeboat, assuming one had been offered to you? At this early hour, it is doubtful. Now it becomes easier to understand why only 705 people found their way into boats meant to hold 1,178. A tragically misguided trust in the ship caused a far greater devastation than was necessary.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home